When I was growing up in Los Angeles, the way my family finished Passover was very different from how most of my friends’ families did. My peers were mostly Ashkenazic Jews, and as the holiday ended, their parents would dutifully pack away their Passover dishes for another year.

In our small West Hollywood apartment, though, something magical was happening.

My parents — immigrants from Morocco and Algeria — were gearing up for one of the highlights of our family’s Jewish year, a remarkable celebration called Mimouna.

Rooted in the Jewish communities of North Africa, Mimouna, which falls on the night when Passover ends, is one of Sephardic Judaism’s most beautiful celebrations. For our family, it was an all-night party. My mother, dressed in a beautiful kaftan, would lay out a sumptuous spread of Moroccan sweets on our Mimouna table — marzipan pastries, dates and fried dough pancakes dipped in honey called moufleta, to name just a few. My father would crank up Arabic music or an Enrico Macias album on the stereo. We’d swing open the doors and welcome scores of guests: fellow Moroccan Jews, Holocaust survivors from Eastern Europe, Israelis, Muslims, Christians and a fair share of neighbors who just wanted to see what the excitement was all about.

From those modest beginnings in the homes of families like ours, the sweet magic of Mimouna has grown in recent years into a far larger phenomenon. When Mimouna arrives the night of April 27, Mimouna celebrations will take place across Israel in homes, public parks, gardens and city streets. Here in Los Angeles, too, and around the country, congregations and communities, both Sephardic and Ashkenazic, will join in the festivities.

How did a Moroccan Jewish festival with origins shrouded in mystery grow into such a popular celebration? What is it about Mimouna — an open house party featuring lavish sweet tables, Andalusian Arabic music, colorful caftans and Judeo-Arabic blessings — that has created a buzz in Jewish communities and penetrated the heart and soul of Israeli society?

Hefzi Cohen-Montague has one answer. “I think all Israelis enjoy Mimouna, because what’s there not to enjoy?” she said. “Sweets, delicious foods, music, happiness — it’s all positive.” Cohen-Montague grew up in the small Israeli coastal town of Givat Olga. “As a child, we went ‘Mimouna hopping’ from one house to the other, but it was exclusively our North African neighbors and friends,” she recalled. “Ashkenazi Israelis were not part of our Mimouna experience.”

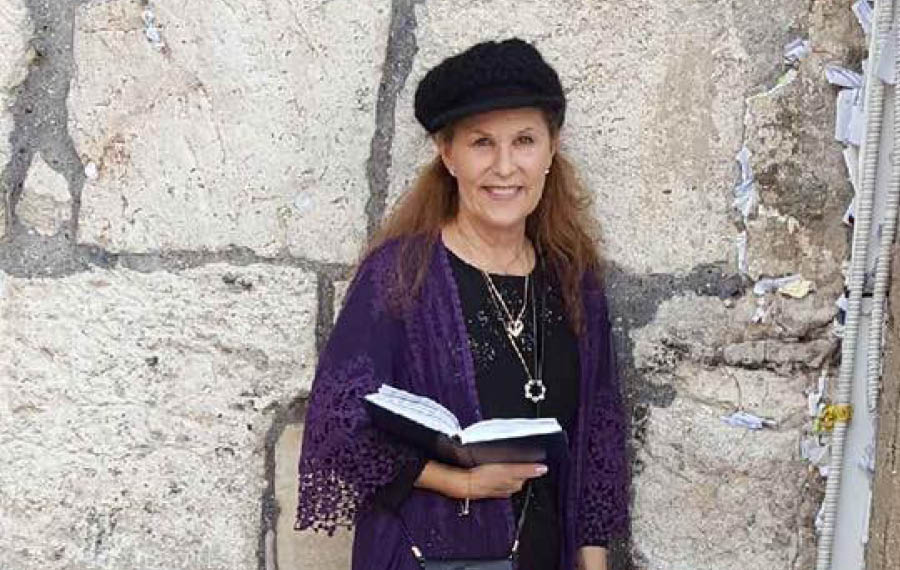

Today, Cohen-Montague hosts one of the largest Mimounas in Jerusalem, with people of all backgrounds and ages mingling and celebrating together. She said the event’s growth reflects the evolution of her place as a Sephardic Israeli woman: “We’ve come a long way in Israeli society, from the days when Moroccans were viewed as second-class citizens, to all Israelis now wanting to come celebrate our festival with us.”

An active participant in an egalitarian Sephardic minyan, Cohen-Montague welcomes another aspect of her celebration: men joining the women to help mix the dough and fry it in oil to make moufleta, the crunchy pancakes dripping in honey that are the culinary centerpiece of Mimouna.

This year, Cohen-Montague’s Mimouna was advertised on Facebook and three Israeli organizations are co-sponsors: Tikkun (a Mizrahi-based movement for social change), Ha-Yeshiva ha-Mizrahit (a Mizrahi-based Torah study group for young Israelis) and Congregation Degel Yehudah (Israel’s first-ever Sephardic-egalitarian minyan in Jerusalem). The three groups have joined forces to help spread the magic of Mimouna to as large and diverse an audience as possible.

Figuring that having so many sponsors would make for an especially large gathering, I asked Cohen-Montague where this year’s Mimouna would take place. She seemed surprised by the question. “In my home!” she said. “Where else would you hold a Mimouna — in a public social hall? Mimouna is first and foremost about opening up your home, and no matter how many people show up, there’s always plenty of room and food for everyone.”

That’s part of the sweet magic of Mimouna: There are no formal invitations, and food is abundant and seemingly endless. The traditional greeting at Mimouna is Tirbah u’tissad (May you prosper and succeed), and it seems that the aura of prosperity and success hovers over every Mimouna.

Photo from depositphotos.com

Of course, Cohen-Montague said she also cherishes the values that make Mimouna particularly attractive to contemporary Israelis. “Unity, acceptance and tolerance amongst Jews, and especially the value of cordial relations between Jews and Arabs, are all central to the Mimouna,” she said. “We open our Mimouna to all Israelis — Jews of all backgrounds as well as Muslims. Most Israelis are tired of living in a polarized, war-torn society, and Mimouna offers an experience when all of that goes away, at least for one night.”

That unifying quality goes back to Mimouna’s roots, said Rabbi Eliyahu Marciano, Israel’s foremost expert on the holiday. “In Morocco, at the conclusion of Passover, our Muslim neighbors would come to Jewish homes with leaves of fresh Sheba vine and nana (mint), flour, milk, honey and sometimes fresh fish,” he recalled. “They helped us launch Mimouna, would wish us a blessed and successful celebration, and then asked for one of us to bless them.”

Marciano has written three books on Mimouna, one titled “Mimouna: The Holiday of Reconciliation and Reunification.” Those timeless themes have particular relevance today, he said: “We had cordial relations with our Muslim neighbors in Morocco, and Mimouna serves as a powerful reminder of that today for all Israelis.”

When I asked Marciano about Mimouna’s origins, he offered several theories, including that Sephardic exiles from Spain brought the custom to Morocco in the 15th century. But when I probed further, he told me I was asking the wrong questions. The proper way to experience Mimouna, he said, is not to ask where it comes from, but rather to understand its symbolism and spiritual depth.

“Mimouna is first and foremost about opening up your home, and no matter how many people show up, there’s always plenty of room and food for everyone.”

— Hefzi Cohen-Montague

Marciano compared it to the widespread custom of ending Shabbat with a melaveh malkah — a gathering to escort the departing Sabbath Bride — and Simchat Torah, the joyous celebration of Torah that follows the weeklong festival of Sukkot. “We started Passover by saying, ‘Let all who are hungry come and eat,’ and we end this joyous holiday of redemption in a celebratory fashion, by once again opening our homes and inviting everyone in to eat and celebrate,” Marciano said.

While Marciano’s books helped document Mimouna’s history and customs for Israel’s traditional/observant communities, a new book shares Mimouna with a wider audience. Its author, Rabbi Dalia Marx, is not Moroccan, and she did not grow up celebrating Mimouna. A 10th-generation Jerusalem native, Marx is an Israeli Reform rabbi with a doctorate in liturgy who teaches at the Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion in Jerusalem.

Aimed at a contemporary Israeli audience, her book, “Ba-Zeman (About Time): Journeys in the Jewish-Israeli Calendar,” is a month-by-month survey of the traditional Jewish holidays and modern-day Israeli observances. I asked Marx what motivated her to include Mimouna. “In the spirit of what Mimouna stands for — inclusion — I felt that it was time to include this rich, beautiful and meaningful holiday,” she said. “Today, Mimouna is a well-established part of the tapestry of Israeli celebrations.”

Mimouna’s inclusion in such a book reflects a sea change in Israeli society. The culture of Marx’s childhood sought to create a uniform Israeli, and Mimouna did not fit into that Israel’s heavily Ashkenazi-Eurocentric narrative. Mimouna’s new popularity reflects how today’s Israel fosters ethnic pride for people of various Jewish backgrounds.

“Today’s bigger question is not whether or not we celebrate Mimouna, but should Mimouna remain a Moroccan festival that the rest of Israelis are invited to, or should it become an official Israeli holiday?” Marx writes. While she does not have a definitive answer, the fact that this is even a question shows how big Mimouna has become.

Marx’s book beautifully brings to life the vibrant features that adorn a traditional Mimouna table. These include a whole fish, a bowl of flour topped with gold coins, dairy products, honey, dates, a colorful array of marzipan sweets and pastries, tea with mint, mahya (Moroccan arak) and, of course, the tasty moufleta pancakes. The custom is to line the table with flowers and green leaves, and the tablecloth often has an elaborate mosaic design. These foods and decorations are symbols of fertility, prosperity, abundance and sweetness, all reflecting the Tirbah u’tissad Mimouna greeting.

“Mimouna has a uniquely feminine vibe,” Marx said. “Preparing for Mimouna is a traditional bonding space for women, and they take tremendous pride in the tables they prepare.”

In a newly produced YouTube video on the holiday, Neta Elkayam elaborates on the woman’s touch at Mimouna. “The Mimouna table goes far beyond just setting a holiday table,” said Elkayam, a multidisciplinary artist and world-renowned Israeli-Moroccan singer. “It’s a culinary work of art, an artistic display of colorful desserts that every Moroccan woman creates with pride and love. Egalitarian values are great, but this one belongs to women!”

Elkayam feels that Mimouna offers Israelis a glimpse into a distinct strain of Judaism, far from the mainstream narratives of discrimination and oppression. “Moroccan Jewry’s narrative is not one of trauma or persecution,” Elkayam said. “Through our Mimouna, we offer Israelis a non-traumatized Judaism of sunshine, warm desert climates, joie de vivre and cordial relations with our non-Jewish neighbors. We invite all Israelis to come experience this type of Judaism, as we feel it could provide a healthier narrative going into the future.”

Meir Buzaglo shares her perspective. The son of the Moroccan composer and singer Rabbi David Buzaglo, he is a professor in Jewish philosophy at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and chairs the social justice organization Tikkun. He calls Mimouna “one of Moroccan Jewry’s greatest contributions to Israeli society.”

With others from Tikkun, Buzaglo has helped spread Mimouna to cities and communities all over Israel, creating themed Mimounas centering around music, Torah study and dialogue groups. One this year is a joint Jewish-Bedouin Mimouna. “Our goal is to turn Mimouna into a transformative day of Israeli unity, and we have even bigger plans for Mimouna 2020,” he said.

Mimouna’s practice and message also are spreading in Jewish communities outside of Israel. Public Mimounas around the United States this year include a celebration at New York’s 14th Street Y and the Israeli-American Council’s Mimouna at the Solomon Schechter Day School in Newton, Mass. Synagogues planning Mimounas include Magen David Sephardic Congregation in Rockville, Md. (known as “The Sephardic Synagogue of the Nation’s Capital”), and Kahal Joseph Congregation, an Iraqi-Sephardic synagogue in West Los Angeles. In the Bay Area, JIMENA (Jews Indigenous to the Middle East and North Africa) is partnering with Urban Adamah (an educational farm and community center in Berkeley) for its annual Mimouna.

It’s striking that none of these Mimouna celebrations is sponsored or hosted by Moroccan Jewish organizations or synagogues. In communities that have long been dominated by Ashkenazic customs, Mimouna now invites Jews of all ethnic backgrounds to taste and feel the flavors, sounds and aura of North African Sephardic Judaism.

Rabbi Sarah Bassin of Temple Emanuel of Beverly Hills, a Reform congregation, is what I call an “Ashkenazic Mimouna Pioneer.” In 2015, her first year at Emanuel, she was looking to build a creative forum in which her synagogue’s young professionals could meet and interact with young professionals from other Jewish organizations in Los Angeles.

In partnership with JIMENA, Sinai Temple’s ATID, the American Jewish Committee and a host of other organizations, Bassin started “Mimouna LA.” In a converted warehouse space, the team created a Mimouna decked out with all of the traditional décor, music and foods. One added feature: booths representing various organizations, to give young professionals the chance to explore L.A.’s diverse Jewish community.

In U.S. communities that have long been dominated by Ashkenazic customs, Mimouna now invites Jews of all ethnic backgrounds to taste and feel the flavors, sounds and aura of North African Sephardic Judaism.

“I wanted young professionals to feel what Moroccan Jewry experiences by going from home to home on Mimouna — I wanted them to feel comfortable going from organization to organization,” Bassin said. “People loved the open and inviting aura that Mimouna provided, and one of the most powerful parts of the evening was that the majority of the 300-plus attendees were not Moroccan, Sephardic or Mizrahi.”

For all the excitement about such public Mimouna celebrations, Esther Malka of North Hollywood, for one, still sees the home as the best place for a Mimouna. Born and raised in a Moroccan home in Israel, Malka migrated with her family to Los Angeles in the 1970s, when she was 11 years old. At first, the family felt alone and isolated, especially the night of Mimouna. “There wasn’t the large community we have here today,” Malka said. “My mother prepared the same beautiful Mimouna table she did in Israel, but missing were the hundreds of guests coming in and out of our house.”

For the past 28 years, Malka and her husband, Haim, have hosted a beautiful Mimouna that now attracts over 300 guests. “I’m proud to have successfully recaptured the aura of Mimouna I grew up with in Israel,” she said. “I love seeing so many guests — Sephardic, Ashkenazic, Israeli, American, religious and secular — all enjoying the sweets, the music and the joyful atmosphere.”

Malka is particularly motivated by her four children and two grandchildren, who eagerly anticipate the event each year. “I feel great knowing that by my doing this, Mimouna will carry on well into the future within my family,” she said.

Hearing that, I couldn’t help but think of my own family’s celebrations back in our West Hollywood apartment. Who could have guessed back then that Mimouna would reach blockbuster status, becoming a national holiday in Israel and a celebration marked by Diaspora Jews of all backgrounds? To paraphrase the traditional Mimouna greeting, the celebration itself has found prosperity and success. Tirbah u’tissad.

Rabbi Daniel Bouskila is the director of the Sephardic Educational Center and the rabbi of the Westwood Village Synagogue.