Tested so far on mice, Dr. Eitan Okun’s vaccine targets amyloid beta protein, which clusters in the brains of people affected by the deadly disease.

APRIL 16, 2018, 8:42 AM

Alzheimer’s disease, affecting some 47 million people worldwide, for now remains an irreversible and fatal brain disorder. Taking a proactive approach, an Israeli

brain researcher is developing a vaccine against this devastating disease.

brain researcher is developing a vaccine against this devastating disease.

Most vaccines work by mounting an immune response toward a weakened pathogen to boost the immune system’s ability to fight the real pathogen. Prof. Eitan Okun’s vaccine primes the body to attack amyloid beta protein accumulations in the brain, one of the signature signs of Alzheimer’s disease.

Experiments on mice in Okun’s Paul E. Feder Alzheimer’s Research Lab at Bar-Ilan University in Ramat Gan reportedly have shown great promise.

He is now preparing to design human trials on people at known risk of developing the disease in their 50s or younger: those genetically inclined toward Alzheimer’s and people with Down syndrome.

“These critical trials will determine whether the vaccine actually works in humans,” said Okun, who also is investigating why people with Down syndrome are more apt to develop Alzheimer’s. The mice he used in his experiments were engineered to mimic Down syndrome.

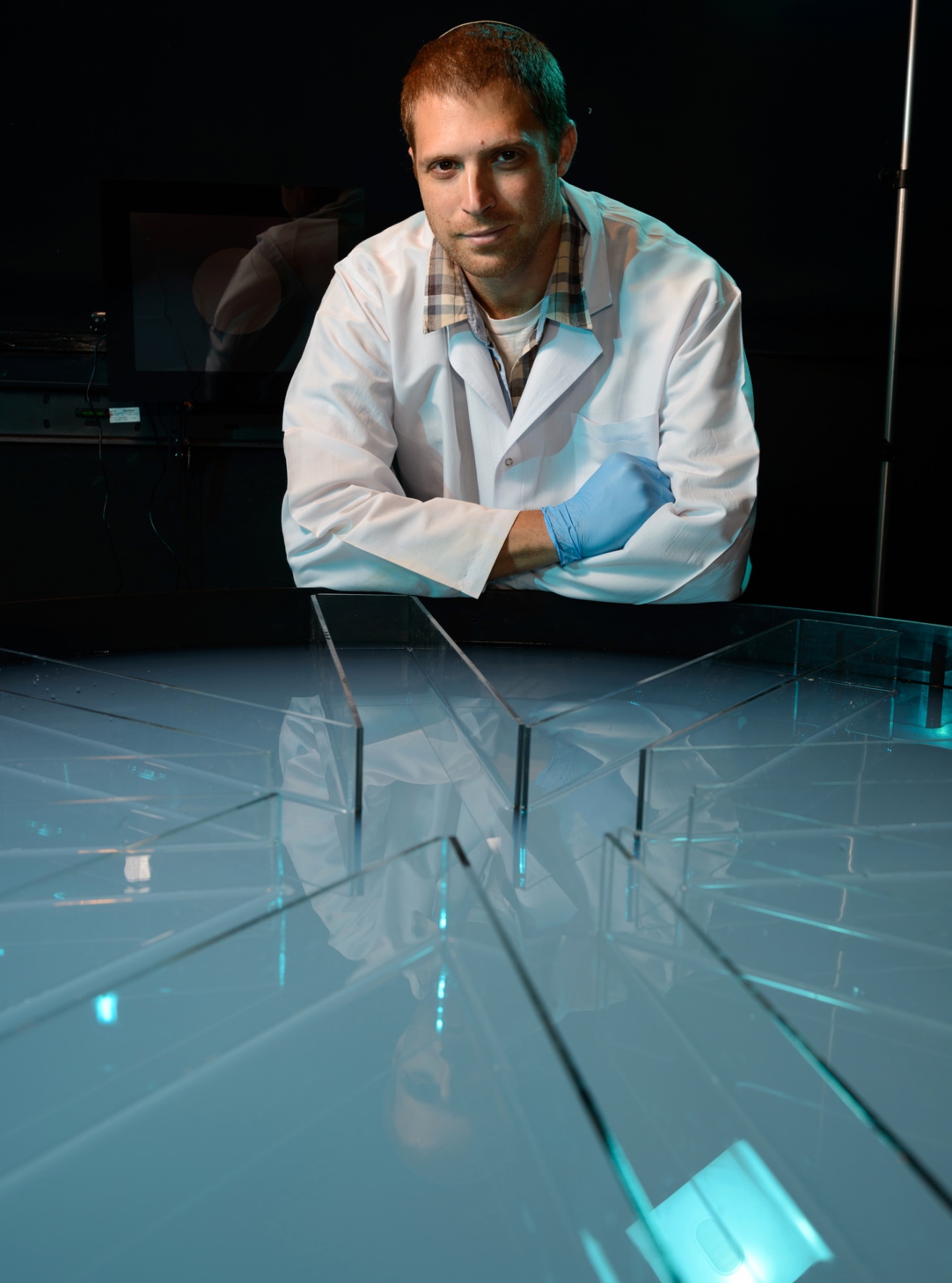

Eitan Okun, Alzheimer’s disease researcher at Bar-Ilan University. Photo: courtesy

“Depending on the success rate and side effects from [human] testing, we will be able to know how much more time is needed to make the vaccine available on a global scale. I am convinced that a vaccination approach is the way to go with neurodegenerative diseases,” said Okun.

In addition to his potentially groundbreaking vaccine, Okun is investigating new ways to diagnose Alzheimer’s earlier and more accurately using advanced MRI technologies to detect initial signs of amyloid protein clumps in the brain.

“My researchers and I have been seeking to construct a protein that could enter the bloodstream, make it through the blood-brain barrier, bind to the amyloids and then be visible in an MRI scan,” he said.

“I am always looking for new angles to attack this disease. I have never been more optimistic that prevention of the disease will be achieved.”

Targets for early intervention

Okun, 39, earned his master’s and doctorate in immunology at Bar-Ilan and did a post-doctoral fellowship at the National Institutes of Health in the United States.

He is a senior lecturer in both the Leslie and Susan Gonda (Goldschmied) Multidisciplinary Brain Research Center and the Mina and Everard Goodman Faculty of Life Sciences at Bar-Ilan.

Aside from his vaccine, he advises that a combination of physical exercise and environmental stimulation can help the brain ward off Alzheimer’s disease by increasing and strengthening the connections of the dendritic spines, which mediate our capacity to generate memories.

“In our lab we use multidisciplinary techniques to pursue two goals: to identify the neural mechanisms associated with mild cognitive impairment, and, at the same time, to look for signposts that would allow physicians to identify at-risk patients, so they can receive preventative treatment for dementia before it’s too late,” said Okun.

He also studies ways to better prevent and diagnose other neurological conditions, such as Parkinson’s disease.

“There is currently no cure for neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, and medical science can only identify such conditions behaviorally – through the symptoms that indicate that brain tissue has already been destroyed,” he explained.

“Our challenge is to find the clues in molecular biology and biochemistry of the brain that would indicate there’s a problem, and would also give us possible targets for early drug intervention.”

Although he has been studying the brain for many years, Okun gained a personal perspective on the importance of neurodegeneration research when his father was diagnosed with dementia in his 60s.

“By the time the changes in his motor and cognitive function became apparent, the brain tissues were already lost. It is my hope that, by gaining a fuller understanding of what happens to our brains as we age, we will be able to help more people live a fuller, more cognitively healthy life.”

No comments:

Post a Comment