Among escalating violence against Jews in the 1930s, the UK accepted 10,000 child refugees in December 1938 in the 'Kindertransport'.

Next year will be the 80th anniversary of their arrival in Scotland, which received Jewish children throughout 1939.

But what did they do once they arrived, what were they fleeing and what happened after WW2 came to an end?

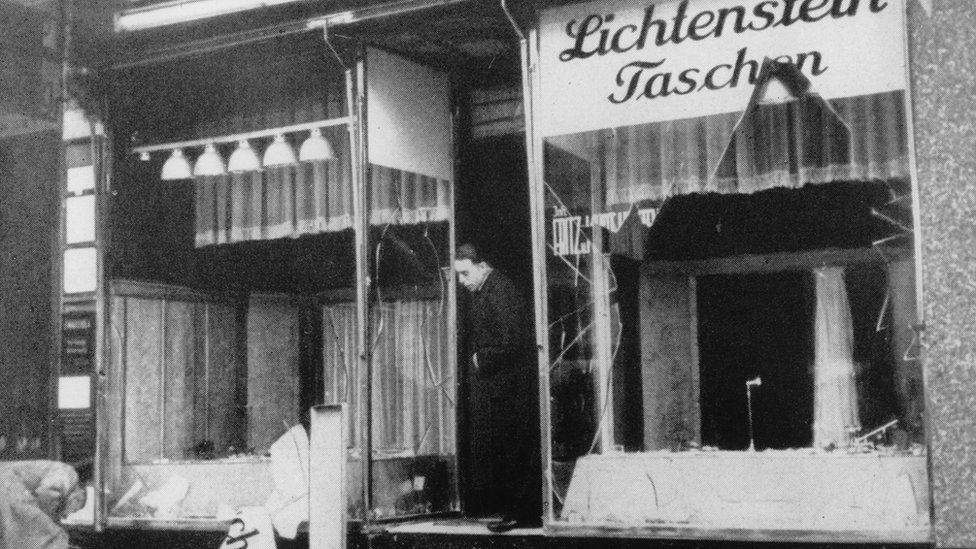

Kristallnacht

The 'Night of Broken Glass' was a significant moment in European history.

Serious, widespread violence against Jews broke out on November 9 1938. It caused the deaths of 90-100 Jewish people, and the arrest and removal to concentration camps of 30,000 Jewish men.

It was sparked by the killing of a German diplomat by a Jewish man in Paris, angry at how his family were treated.

Joseph Goebbels, Reich Minister of Propaganda, did not advocate vigilante action, but stated that if it occurred, nobody should oppose it.

Gangs attacked Jewish businesses, buildings, and synagogues and daubed them with "Juden verboten" (Jews forbidden).

Jewish leaders in London petitioned the then home secretary, Sir Samuel Hoare, to rescue children.

In Westminster, it was decided an unspecified number of Jewish children would come to the UK temporarily as refugees, and that, after hostilities, they would reunite with family.

'A welcoming country'

Many found the journey difficult. Karen Goodman's mother, Margit (now deceased), said how thankful they were when the train passed through Holland after departing Prague.

She said: "Mum told me how amazing it was that women came on with hot milk and bread. She remembered they were quite hungry by that stage."

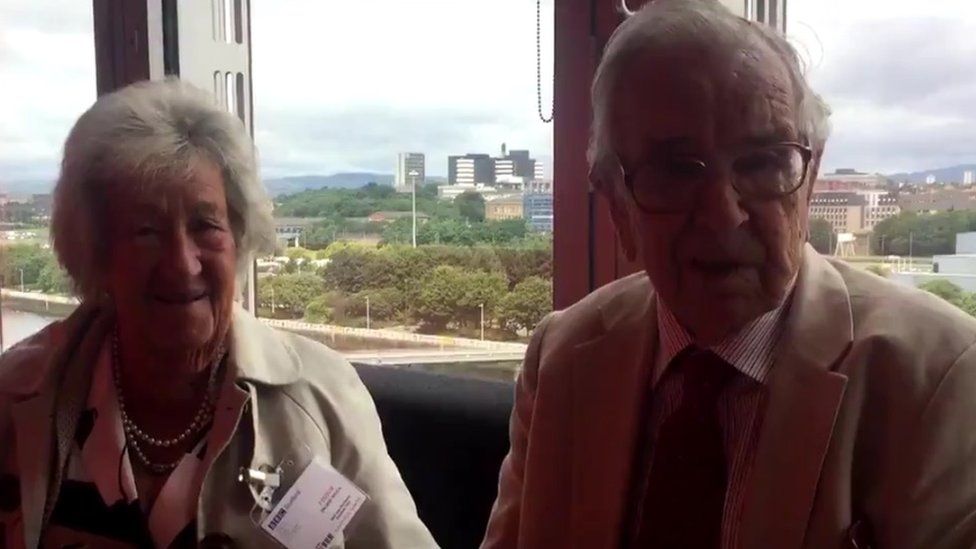

Henry Wuga came to London and then Glasgow on a train in May 1939. He lived with an older Jewish lady in Glasgow.

"You're coming to a country with a different language and culture. Whether it was Wales, England, or Scotland, it didn't matter - I was glad to be here," he said.

Mr Wuga was made to feel "very welcome" by his host.

"Within a few weeks I was at school - Queen's Park School [in the Battlefield area of Glasgow].

"Nobody was abusive because we were German, or because we couldn't speak proper English, or were Jewish. On the contrary, people were very kind."

Mr Wuga's mother had previously sent him to the Black Forest to become an apprentice chef.

"She said - 'You have to learn a trade. When you leave this country you have to earn a living'."

He spent six months learning in Baden-Baden until Kristallnacht forced him to leave in May 1939.

Mr Wuga said, having lived away from home, "leaving home again was not new, don't get me wrong - I didn't like leaving home, but I knew I faced the world once before".

'57 varieties'

Mr Wuga even got an interesting nickname from his peers.

"You know, my name was not Henry - it was Heinz . So at school I was called '57' - you know, 57 varieties!"

This adjustment to fit in was an experience shared by other kindertransportees.

Robert Arlan says his father left Berlin three days before Robert's 18th birthday, changing his name and the family name from Manfred David Aronsohn to Fred Arlan.

Robert said his parents made the name up. "There are no more Arlans in the UK!" he added.

Scottish-cised

Stefan Paul Ludwig Brienitzer came to Edinburgh.

One factory manager approached him saying: "Please, change your name to something I can pronounce!"

Stefan Brienitzer, as he described at the John Gray Centre , became Stephan Brent - something he called "anglicised - or Scottish-cised".

This was not always the case. Margit Goodman's kept her Czech name.

Karen Goodman, her daughter, said: "There are many stories of children who reunited with their families but the gulf between them was unbridgeable.

"Children could no longer speak German or Czech nor the parents English."

She continued: "Children became anglicised. Many went to Christian homes and lost that [connection to families with] religion."

Did they reunite?

Often, children who came to the UK did not reunite with families as parents had been killed in concentration camps.

Stephan Brent, whose story is documented on East Lothian at War , discovered what happened to his family after the war.

"They were killed in Auschwitz and my grandmother was taken to ... Treblinka where she too was killed," he said.

His mother smuggled messages off a train from Breslau to a girl loading suitcases, who subsequently went to live in Palestine.

"My Israeli half-brother's daughter was doing PhD research on the Jews of Breslau. When looking through papers she came across my mother's note - an unbelievable coincidence."

'Scotland's my country'

Many who came to the UK settled after the war. Despite the temporary nature of the arrangement, many remained.

Margit Goodman had been "put into service" and was an untrained nurse in Glasgow during the war. She then moved to Hertfordshire.

"After the war [my mother] went to Prague to see who had survived. That's where she met my father, a trainee journalist working with a paper called 'The Soldier'," said Mrs Goodman.

After marrying, Margit moved to London and spent her life there.

Mr Wuga stayed in Scotland.

"I was a chef de cuisine [in Germany] so I worked in restaurants and hotels in Glasgow.

"Eventually with my wife [Ingrid - also a kindertransportee] we founded our own catering business that we had for 30 years."

Mr Wuga, after leaving catering, volunteered with Blesma, helping limbless veterans to ski, for which he received an MBE.

"I find that Scotland is my country now," he says "I love the country."

No comments:

Post a Comment